1685-1700: Eisenach and the family heritage

To start at the very beginning, Bach was born into a very long line of musicians. The opening words of the obituary written by his second son Carl Philipp Emanuel in collaboration with Johann Friedrich Agricola tell us so: ‘Johann Sebastian Bach belongs to a family that seems to have received a love and aptitude for music as a gift of nature to all its members in common. So much is certain, that Veit Bach, the founder of the family, and all his descendants, even to the present, seventh generation have been devoted to music, and all save perhaps a very few have made it their profession.’

We know that Bach was deeply interested in his predecessors because he himself constructed a family tree of musical Bachs going back many generations. It is a strange family tree in that it names no female members. Perhaps this was inevitable at the time, although Bach’s second wife, Anna Magdalena, was a fine singer, and Bach admitted that his first daughter Catharina sang tolerably well.

‘Johann Sebastian Bach was born in 1685, on March 21, in Eisenach. His parents were Johann Ambrosius Bach (1645-1695), court and town musician there, and Elisabeth, née Lämmerhirt, daughter of a town official in Erfurt’, says the obituary. His place of birth is significant, for it was in Eisenach that Martin Luther was in part educated, and translated the New Testament into German. At his death, Bach’s library contained not one, but two editions of the complete writings of the great theologian. The figure of Luther and Bach’s Lutheran faith would be a constant source of strength and inspiration throughout his life.

Bach’s father was the director of the town musicians and played several instruments (although probably not the organ). It is interesting to note that the young Johann Sebastian was often absent from school in his early years. We might presume that he was away helping his father and in so doing, experiencing his first music making.

The obituary continues: ‘Johann Sebastian was not ten years old when he found himself bereft of his parents by death. He betook himself to Ohrdruf, where his eldest brother, Johann Christoph [1671-1721], was organist, and under this brother’s guidance, he laid the foundations for his playing of the clavier. The love of our little Johann Sebastian for music was uncommonly great even at this tender age.’

Elisabeth died on 1 May 1694, and Ambrosius on 20 February 1695. Johann Sebastian’s brother Johann Christoph had studied for three years with the famous Pachelbel, and had developed a keen interest in French organ music as well as the composers of the great north German tradition. All this would strongly influence the young Johann Sebastian.

1700-1703: Lüneburg

‘[In 1700,] Johann Sebastian betook himself, in company with one of his schoolfellows named Erdmann . . . to the St Michael Gymnasium in Lüneburg . . . [where] because of his unusually fine soprano voice, [he] was well received.’

Lüneburg was important, not only for the quality of the school choir and the extensive music library, both of which must have reinforced Bach’s musical development, but also for the visits of the famous orchestra from Celle, which was staffed almost exclusively by French musicians who performed their native repertoire. It was important actually to hear French musicians play, for the notation gives only a pale impression of how vivid this music is in sympathetic hands.

From Lüneburg, Bach also travelled to Hamburg, where he heard the famous organist Johann Adam Reinken, who would be an important influence on his organ music. Although it is not mentioned in the obituary, it is difficult to imagine that, during these visits, Bach would have completely ignored the thriving opera house in Hamburg, where George Frideric Handel was soon to begin his operatic career.

‘In the year 1703, he came to Weimar, and there became a musician of the Court.’

Finally, at the age of seventeen, Bach began to earn his living – not in church, but at court, and, most likely, predominantly playing the violin rather than the organ. This employment, however, would last only a few months before Bach was appointed organist of the New Church in Arnstadt in August of the same year. He had been called to examine the new organ there, in June or early July, and had apparently impressed the people of Arnstadt. This was obviously a resounding endorsement of the abilities of a young man who had just turned eighteen, but it should be mentioned that the Bach name was not unknown in Arnstadt. At least seven Bachs had been town musicians or organists there before 1703. The Bach reputation and a certain level of family influence was most probably at work in the young Johann Sebastian’s first posting.

1703-1707: Arnstadt. Bach the organist

C.P.E. Bach tells us: ‘The next year, he received the post of organist in the New Church in Arnstadt. Here he really showed the first fruits of his application to the art of organ playing and composition, which he had learned, chiefly by the observation of the works of the most famous and proficient composers of his day, and by the fruits of his own reflection upon them.’

Arnstadt was not to be quite the dream appointment that he might have imagined. Bach was nominally in charge of a group of students many of whom were several years older than he was. He clearly had a problem with authority. He refused to play or compose for the ensemble, insisting to the authorities that he was the organist, and not the music director (although such a distinction was difficult to justify), and on one particular occasion, on 4 August 1705, had a street fight with a bassoonist named Geyersbach.

This was far from the only complaint levelled at Bach. It was from Arnstadt that he made his famous journey to Lübeck . . .

‘Johann Sebastian Bach, organist here at the New Church,

appeared, and stated that,

as he walked home yesterday,

fairly late at night,

coming from the direction of the castle,

and reaching the market square,

six students were sitting on the Long Stone,

and as he passed the town hall,

the student Geyersbach went after him with a stick . . .’

– from the Proceedings of the Arnstadt Consistory

‘While he was in Arnstadt, he was once moved by the particularly strong desire to hear as many good organists as he could, so he undertook a journey, on foot, to Lübeck, in order to listen to the famous organist of St Mary’s church there, Dieterich Buxtehude. He tarried there, not without profit, for almost a quarter of a year, and then returned to Arnstadt’ (obituary).

The authorities in Arnstadt did not look on Bach’s voyage in quite such a positive spirit. The Consistory reproved him for an absence of four months, when it had been agreed that he should be absent for four weeks.

Had he gone to Lübeck with the intention of proposing himself for the post of Buxtehude, who was by then nearly seventy years old? If so, he may have been discouraged by the condition (not uncommon in the appointment of organists at the time) that he must marry Buxtehude’s eldest daughter, ten years older than the twenty-year-old Bach. However that may be, Buxtehude’s eventual successor did indeed marry her.

In Arnstadt, Bach was also criticised for playing the chorales in such a chromatic way that the congregation became lost, for playing for too long a time, and finally for having introduced a young woman into the organ loft. This last criticism is interesting, since we know that soon afterwards Bach was to marry a distant cousin who shared the same name, Maria Barbara Bach.

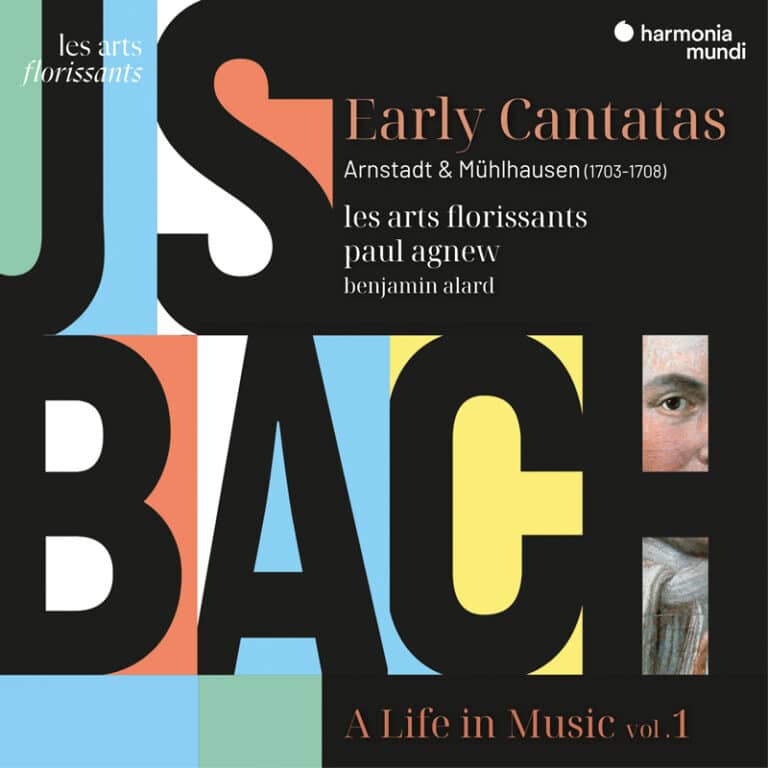

It is now thought that we have no cantatas from the Arnstadt period. The cantata previously ascribed to Arnstadt, BWV 150 ‘Nach dir, Herr, verlanget mich’ (recorded in volume 1, tracks 21 to 27), has now conclusively been placed in Mühlhausen.

Clearly Bach had exhausted his welcome in Arnstadt and needed to find another post. Conveniently (at least for Bach), the organist at St Blasius’s church in Mühlhausen had died in December 1706, and by April Bach was auditioning for the job. This event fell on Easter Sunday 1707 and it is very possible that Bach’s audition cantata was BWV 4, ‘Christ lag in Todes Banden’ (recorded in volume 1, tracks 1 to 8). He was appointed organist on terms considerably more favourable than those enjoyed by his predecessor (as had already been the case in Arnstadt) on 15 June 1707 at the age of twenty-two. Four months later Bach was married.

1707-1708: Mühlhausen. The first cantatas

‘In the year 1707, he was called as organist to the church of St Blasius in Mühlhausen. But this town was not to have the pleasure of holding him long.

. . . Our Bach was married twice. The first time with Mistress Maria Barbara, youngest daughter of the above-mentioned Johann Michael Bach, a worthy composer. By this wife he begot seven children, namely, five sons, and two daughters, among whom were a pair of twins.’

They were married on Monday 17 October 1707. As the obituary suggests, Bach was not to remain long in Mühlhausen. By 1708 he was organist in Weimar.

Whatever the precise length of time Bach stayed in Mühlhausen, where most of the cantatas on this recording were first given (the early cantatas are very difficult to date precisely) he produced music that is not only sublime, but truly original in character.

Nevertheless, we can only imagine that resources were limited in Mühlhausen. It is interesting to note that, for the cantata Gott ist mein König BWV 71 (not recorded in our project), which Bach wrote in 1708 for the annual service held the day after the council elections, he had four instrumental choirs available: Choir 1 consisting of three trumpets and drums; Choir 2 of two recorders and cello; Choir 3 of two oboes and bassoon; Choir 4 of two violins, viola and violone.

If we set aside the trumpets and drums not required by the cantatas chosen for this recording, we actually have all the instruments necessary for the cantatas on our programme, with a single player to each instrumental part. Further to this, Bach’s autograph score for BWV 71 informs us that it is possible (and perhaps preferable for him? If not, why would he have suggested it?) to have four vocal soloists (concertists) and four further singers (ripienists) who are optional. I have based our ensemble for Volume 1 on this configuration, with solo instrumentalists, four soloists and a further four singers for the choruses. The question of vocal forces has remained very difficult to resolve with any degree of certainty since the research of Andrew Parrott and Joshua Rifkin, and I don’t suggest that my solution is in any way a definitive answer. It is a proposition (originally made by Bach himself) which seems to work well in giving relief and variety to the music while not adopting a ‘choral’ sound.